2021vii31, Saturday: Ours, theirs, and attribution.

Our minds play tricks on us. All the time. One trick is particularly pernicious - but recognising it can change the world.

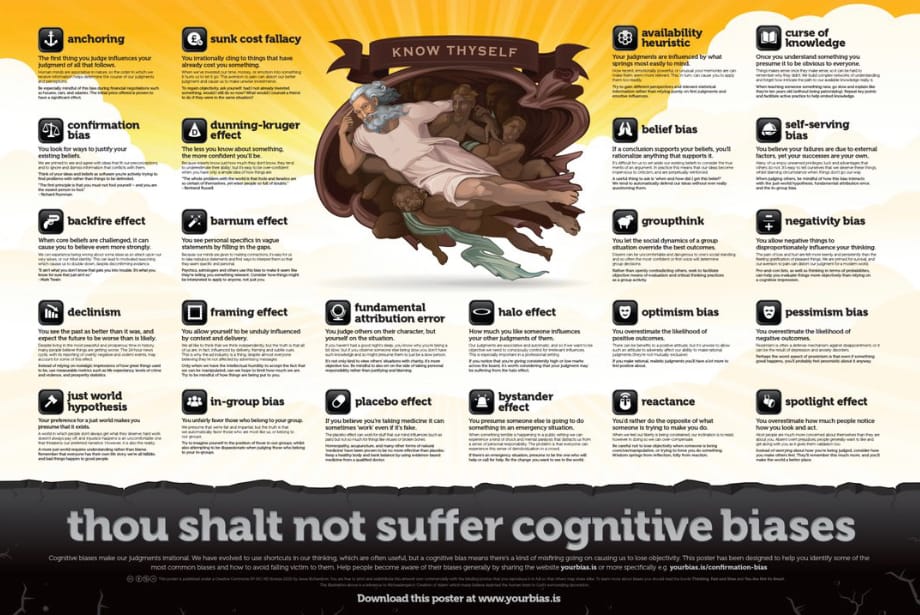

I’ve long been fascinated by cognitive biases and logical fallacies: the tricks our minds play on us, driven deep within our psyches like paths trodden across hillsides over centuries of traversing feet. I have posters on my home office wall listing many of the most common ones. And when I was at StanChart, I built them into a class for new graduate trainees.

In some ways, the fallacies are more fun, not least because some of the names are evocative as hell. The no true Scotsman fallacy. (“That lad in the paper who did the murder. Must’ve been English. No Scotsman would do that.” “No - says here he was from Falkirk.” “Ah - well, no true Scotsman would do that.”) The Texas sharpshooter fallacy. (Just because some set of data makes a neat group, don’t assume a connection. It’s possible the set may have been chosen - deliberately or unconsciously - to fit the hypothesis, like someone shooting at a wall and then drawing the target in afterwards to fit the grouping.) And one that us barristers may be particularly vulnerable to, the fallacy fallacy. (Don’t dismiss a claim just because it’s been poorly argued, or because the explanation for it includes a fallacy. In other words: the best skeleton argument, the best advocacy, is sometimes going to fail if the other side’s underlying case is - well - just better. Not always, thank goodness, otherwise we’d be out of a job. But sometimes.)

But the cognitive biases are more pernicious. And one in particular has a devastating effect - not only on us as individuals, but on us as groups. It’s the attribution effect. It was identified by a man named Lee Ross, many years ago. Ross died recently, and I was reminded of this critical bias by a thoughtful and thought-provoking piece of writing about him, about the error, but mostly about just how fundamental it is to understanding where we’re going wrong - and what we can, each of us, do about it.

OK. That was a bit cheeky there, using the word “fundamental”. Because when Ross first identified this, he called it the “fundamental attribution error”. As originally formulated, it referred to our tendency to look at others’ conduct and take it as arising from their character, not their situation. “So that woman over there who didn’t let me into slow-moving traffic? She must be SO selfish. Dread to think what it’d be like to work with her.”

Yes, I know, that’s a simplistic example. But it’s enough to shine a light on what I’m talking about. How often do we look at others, see a snapshot of their behaviour, and take it as a synecdoche of who they really are? And how often do we consider that it might instead just be a moment of thoughtlessness or inattention brought on by a really bad day? A sick relative? An angry boss? An unexpected bill?

Then there’s the flip side, which we customarily apply to ourselves. So we snapped at a waiter. But that’s not us. That’s because he took too long to bring the bill. Or because we have to work this weekend. Or because of that blasted woman who made us late to the restaurant because she wouldn’t let us into traffic.

(There’s another similar bias, the self-serving bias: the tendency to see our errors as down to circumstance or dumb mischance and our successes as entirely down to our own greatness and hard work. I’m sure none of us recognise that one. No. Of course not…)

In psychological terms, this is the difference between dispositional attribution - something that arises from who we are - and situational attribution, which is driven by external circumstance.

I imagine we all recognise it now. It probably feels like just one of those things that make us human. So why am I saying it’s so important, and so pernicious?

Because in a world which seems more and more divided into us and them, in-group and out-group (for me, this will always be the Japanese terms “uchi” and “soto”, which carry huge emotional resonance for any Japanophile), attribution is deadly. We see it all the time: the easy justification of what “our” people do as necessary, external forced upon us by the times, by the circumstances… or of by course the other lot. Whose actions are driven by malice, or by political beliefs which are selfish or evil or at best just plain incomprehensible to real people (however defined). Real people like us.

Meaning that whatever we do, we do reluctantly and in good faith, and with the best of intentions. And whatever they do, they do because they’re just that kind of awful people.

Tell me you don’t see it. Every day. Now tell me you don’t do it. I wish I could. I can’t.

For students of cognitive bias, there are some clear crossovers here, indicating that an uchi/soto split seems to drive large chunks of our psychic plumbing. There’s the halo and horns effect, which means things done by those who’ve made a good impression on you in the past will seem good, whereas things done by those you’ve had reason (perhaps?) to despise will seem bad - irrespective of what either is actually doing. There’s the availability heuristic, where things that are recent, close or present seem more relevant to decision-making, more prevalent, than more distant things - and, of course, those in your immediate group as as close as it gets. And then there’s the old favourite, confirmation bias, where you overweight evidence that confirms your existing beliefs and downgrade evidence that opposes it.

So maybe we’re hardwired to attribution when it comes to our group and theirs. Not surprising, perhaps. But as the writer of the piece I linked to points out, as we atomise more and more, this tendency will burrow deep and destroy us - unless, as with all cognitive biases, we do our best to see it happening in ourselves, rather than just letting it rip.

This is one reason I have so little patience with dog-whistle labels and straw-manning, from whichever side of the political spectrum they arise. The label triggers the attribution: I can stop thinking about that lot, it says, seductively. I know their sort. And I know their motives. Not like us righteous types over here.

Can we stop ourselves doing this? Of course we can’t. Can we strive to mitigate it? Yes. Should we? You’ll need your own answer to that. I know mine.